‘I spent a good part of the summer reminiscing about my time in Nepal for the Eland Newsletter.’

‘How did you do it?’ is a question I’m often asked by people who read Against a Peacock Sky, my account of two years in a remote village in northwestern Nepal in the early 80s. This is often closely followed by a reference to my comment that ‘several times, when I had fleas, lice, worms and diarrhoea all at once, I actually dreamt of a bathroom’.

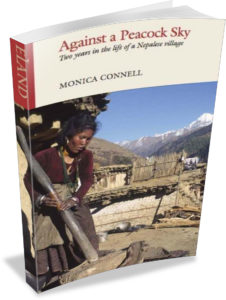

AGAINST A PEACOCK SKY Two Years in the Life of a Nepalese Village – Monica Connell

The village, called Talphi, was ten days’ walk from the nearest road and one from the airstrip in Jumla Bazaar where small aircraft landed sporadically during the winter and never during the monsoon. The reason I was there, with my partner Peter, was to do the fieldwork for a PhD in anthropology. It was partly because of this that my focus in the book is the village and the family who shared its home and life with us, rather than myself and my own emotions.

But to answer this question: it was hard, sometimes very hard, and I’m not sure I could do it now, but with hindsight I feel utterly privileged to have had the experience.

The village had no running water or electricity. The bathroom was the river, drinking water river water, and the toilet was the bushes (or for some the village paths and river banks). For lighting we used splints of pine wood gouged from deep inside the biggest trees. They were almost translucent pink from resin and burned with smoke so black that soon our faces, hands, ankles, books, clothes and sleeping bags were permanently engrained with soot. For warmth and cooking there was a small fireplace in the centre of the room, but no chimney (which would have allowed access for evil spirits), so thick smoke hung in the air, causing our eyes to stream and our heads to ache, until eventually it seeped out under the eaves.

But, for me, these physical hardships were nothing compared to the emotional ones. Before we arrived many of the villagers had never seen foreigners, let alone white ones, so their curiosity was understandable, but I was occasionally reduced to tears when groups of people gathered round us pointing and laughing, reaching out to touch us and talking about us as though we were animals in a zoo. Then, there was the local conviction that we were doctors and had infinite supplies of medicine. It was useless trying to convince people that they needed to go to the hospital (the nearest health post) a day’s walk away, so we did our best with a medical manual and the medicaments we had brought with us and later replenished. But I shudder now to think of the terrible injuries and afflictions that people we knew and cared about trusted us to cure.

But, for me, these physical hardships were nothing compared to the emotional ones. Before we arrived many of the villagers had never seen foreigners, let alone white ones, so their curiosity was understandable, but I was occasionally reduced to tears when groups of people gathered round us pointing and laughing, reaching out to touch us and talking about us as though we were animals in a zoo. Then, there was the local conviction that we were doctors and had infinite supplies of medicine. It was useless trying to convince people that they needed to go to the hospital (the nearest health post) a day’s walk away, so we did our best with a medical manual and the medicaments we had brought with us and later replenished. But I shudder now to think of the terrible injuries and afflictions that people we knew and cared about trusted us to cure.

Perhaps it was because of these general discomforts that small joys took on added proportions: the view from our window of snow capped Patrasi Himal changing with the light from ice blue to golden; our friendship with the family which deepened as our language skills improved; my expeditions with Kali, the ten-year-old daughter and my closest friend, to gather wild strawberries in the forest; a boar-hunt with the village men on a frosty winter’s morning.

This year my friend’s son is on his gap year. A month ago he Skyped his parents from a pizza restaurant in Rajasthan – they saw him sitting there with hazy yellow buildings in the background. As he toured he searched each new destination on his iPhone for yoga classes and cheap restaurants. Now he is in South America travelling with and meeting other young people from London, where he lives, and all over the world. From time to time photos appear on Facebook: a group of school leavers, grinning, pulling faces, happy with their new-found freedom and the possibilities ahead.

But many of these pictures could have been taken anywhere. Television, the Internet, Facebook and other social media are spreading a single culture throughout the world, which is both exploited and driven by multinational companies. Even the most remote communities are losing their unique identities in a bid to modernise and promote tourism.

This is why I feel privileged to have spent those years in Talphi, a village whose culture had barely changed for hundreds of years. The people were subsistence farmers; everything they needed they grew, made, bartered, gathered in the wild, or in the case of animals, bred. Fields were tilled with oxen and wooden plough shares; doors were tree trunks chipped flat with adzes; men’s clothes were typically sheep’s wool, spun, woven and stitched in the village; women’s skirts were tubes of rough cotton printed with a wooden stamp and natural dyes; oil was pressed by hand from wild walnuts and the fruit of thorn bushes; hair was washed with mud, dishes with cinders and ash.

How many cultures like this are left in the world? I haven’t been back to Talphi but Peter tells me a missionary has settled close to the village and many people now wear crosses. This will undoubtedly lead to the demise of the traditional religion and full moon festival when, to the roar of kettledrums, local gods enter the shamans’ bodies to dance and answer questions about sickness, crop failure and family feuds. There is also now electricity, radio and a monthly film show.

Much of this is inevitable and for the better. But as I wheel my supermarket trolley through aisles stuffed with processed and packaged foods from all over the world I sometimes remember the delight on Kali’s face as she offered us a rare bowl of milk in summer, when the cows were yielding, or a handful of wild greens that she had picked in the hills.

I am deeply grateful for my time in Talphi, which changed me profoundly; and I am grateful too to Eland for their commitment to keeping alive accounts of this and other extraordinary places throughout the world.

You can read the article online on the Eland publisher’s website here.